UT History Series: Hall of Fame Football Coach Chelo Huerta

By Joey Johnston

One of the greatest moments in University of Tampa football history occurred on April 29, 2002. It was far from the cheering crowd and marching band. No touchdowns were scored. The UT football program, in fact, was long gone.

But on that day, the call finally came.

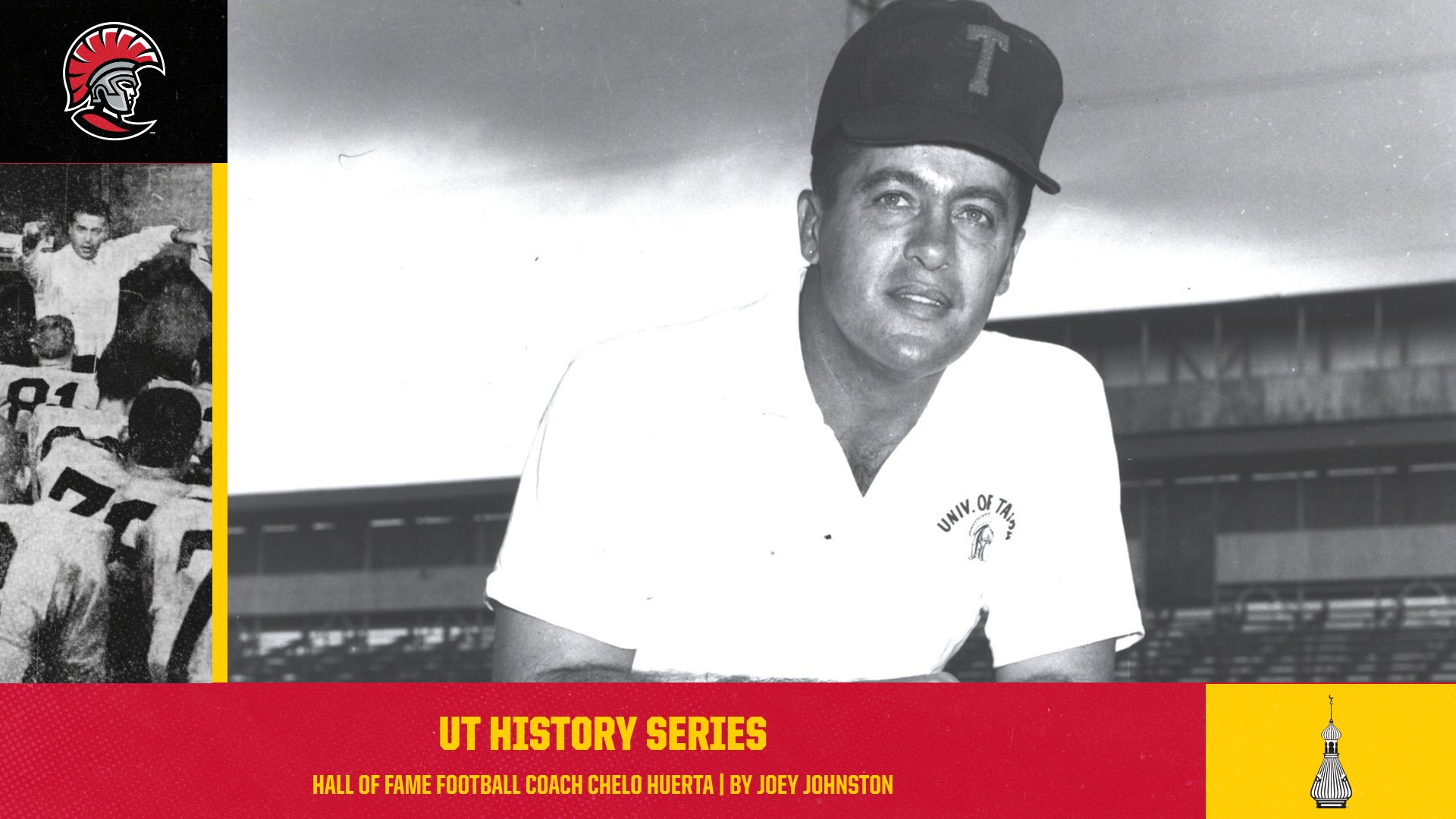

Former Spartans coach Marcelino "Chelo'' Huerta — the pride of Tampa, the son of Spanish immigrants, the ultimate underdog — had been selected posthumously for induction into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Nearly 17 years after his death, following an announcement that would have made him swell with pride, Huerta was officially immortalized. He would not be forgotten.

For fans, observers and players who were in Huerta's orbit, after watching him transform UT into a small-school power from 1952 to 1961, how could they forget?

"With Chelo, you felt you could do anything and beat any opponent,'' said former UT linebacker Tony Yelovich, who became an assistant athletic director at Notre Dame. "We just rallied around everything he said and did. He thought all things were possible.''

At age 28, Huerta became the nation's youngest head football coach/athletic director when he succeeded Frank Sinkwich at UT in 1952. During 10 seasons with the Spartans, Huerta was 63-37-2, including two victories in Cigar Bowl games at Tampa's Phillips Field.

In 16 seasons as a college head coach — at UT, Wichita State and Parsons College, three schools that no longer play football — he was 104-53-2.

Huerta's legacy was more than just football.

Between his playing days at Hillsborough High School (1940-43, captain, All-Southern, All-State) and the University of Florida (1945-49, he was a lineman during the school's so-called "Golden Era,'' when the Gators had a 13-game losing streak), Huerta joined the Army Air Corps and became a decorated bomber pilot in Europe during World War II.

In 1968, despite job offers from Wake Forest and New Mexico State, Huerta retired from coaching. He moved his family back to Tampa and became executive vice president of MacDonald Training Center, which rehabilitated and trained mentally handicapped people. He also served on the President's Council on employment for the handicapped.

Huerta was 61 when he died of a heart attack in 1985. At his funeral, more than 2,000 mourners packed into Christ The King Catholic Church. Hundreds of others were outside. Meanwhile, dozens of cars circled the area, unable to find a parking space.

It spoke to the man, his personality and his legacy.

The late Ferdie Pacheco, best known as Muhammad Ali's fight doctor, grew up in Ybor City and idolized Huerta. "In Tampa, Chelo was royalty,'' Pacheco once said. "With Chelo's charisma, you just wanted to follow him around.''

Huerta's charisma was admired by another up-and-coming football coach, who also considered himself an underdog.

"I'm more like Chelo than I am the Bear (Bryant),'' said former Florida State University coach Bobby Bowden. "Short and scrappy. Sort of an underdog. Chelo always put a smile on my face. I believe everyone really liked him and respected him.''

Especially in Tampa, where he was more than just a successful football coach.

Huerta was a character, using hyperbole to make a point and entertainment to keep everyone in stitches.

Sometimes, he'd escort young players into the athletic offices for a meeting with UT business manager Paul Straub. Huerta would abruptly grab a metal dart and fire it into Straub's leg.

Players might gasp, flinch or even faint.

Straub didn't bat an eye.

"Now THAT is how tough you need to be to play football here,'' Huerta pronounced.

Huerta never told the players that Straub's long pants actually were covering wooden legs. Straub had lost both legs during a land-mine explosion in World War II.

Before a game against heavily favored Delta State, Huerta bragged to the press that 280-pound fullback Fred Cason was the key to UT's game plan. But he didn't say that Carson, in fact, had hurt his back and was hospitalized.

Huerta found a 260-pound tuba player, dressed him in Cason's uniform, and kept him by his side the whole game. Delta State, waiting for Carson's emergence, never adjusted its defense and lost 14-13.

During his early UT coaching days, as legend has it, Huerta apparently suited up and played in some road games.

Miami coach Andy Gustafson inadvertently walked into the Spartans' locker room at halftime. There was Huerta — dirty, bloodied and in full uniform. He had chalk in one hand (to diagram a play) and a cigar in the other.

Gustafson threatened to tell the officials.

Huerta protested, "Gus, you're up 28-0! I play even worse than I coach.''

That swagger and pizzazz continued when Huerta migrated to Wichita State, where he once told a Rotary Club audience that his team would hold Tulsa to a three-and-out in its first series, force a punt, then run the kick back for a touchdown.

Sure enough, Tulsa went nowhere in three plays and punted.

Wichita State returned it for a touchdown — just as Huerta had predicted.

As the crowd went wild, Huerta turned toward the stands and took a bow.

Huerta, the first Hispanic coach inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame, always will be a major part of the UT football story because of his record and the nine players he coached to Little College All-America status.

His work lived on through others.

Huerta helped one of his former Wichita State players, Bill Parcells, get an assistant coaching job at FSU. Parcells won two Super Bowls with the New York Giants and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2013.

While working with Tampa's Lions American Bowl all-star game, Huerta opened a spot for fledgling coach Lee Corso. That became the springboard for Corso's big head-coaching breaks at Louisville and Indiana. Corso became a household name as an ESPN announcer and unforgettable presence on the network's College GameDay program.

Huerta's resume — and the richness of his career — speaks for itself.

His parents — Marcelino Sr. and Josefina — always said he could accomplish anything in America if he worked hard and remained honest.

"Our family is so grateful that his coaching career is still remembered,'' said Huerta's son, Marcelino III, upon receiving news of his father's College Football Hall of Fame election in 2002.

How could it be forgotten?

Joey Johnston has worked in the Tampa Bay sports media for more than three decades, winning multiple national awards while covering events such as the Super Bowl, World Series, Final Four, Wimbledon, the U. S. Open, the Stanley Cup Finals and all the Major bowl games. But his favorite stories have always been about Tampa Bay Area teams and athletes. A third-generation Tampa native, he was a regular in the Tampa Stadium stands at University of Tampa football games.